It's no secret that Canonical is a large proponent of Bazaar (bzr) and would like to use Ubuntu as a guinea pig for large scale deployments. At UDS Prague, James Westby gave an interview about using "distributed version control systems" (DVCS) for coordinating development. The interviewer is a bit confused about how the Ubuntu flavors interact, so I think an explanation of DVCS and Ubuntu development is in order.

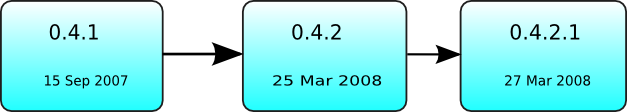

When talking about open source software in general, it's important to keep in mind the concept of versions. Each patch applied to a project can be thought of as a new version of the software. Generally projects release a new version every few months containing a bundle patches. Here's an example based on Xournal:

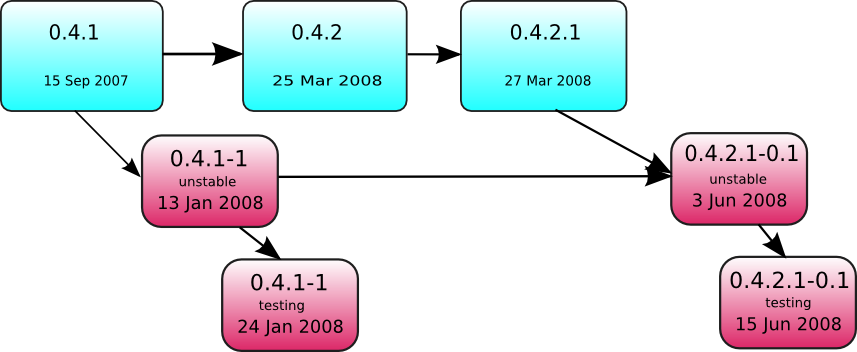

Xournal turns out to be a pretty good scenario so I'll keep returning to it. Time flows from left to right (but not necessarily to scale). Note the time span between 0.4.2 and 0.4.2.1. There was a pretty critical crashing bug that was caught, patched and released there. However, few new users should use Xournal directly from source rather than go through their distribution. For example, Debian provides packages for Xournal. A picture is enlightening. NOTE: This is not meant to encompass the entirety of Debian's release process:

Several things are going on here. I've organized the picture into three rows: upstream in blue and Debian unstable and Debian testing in red. Debian packagers take upstream releases, add control and build rules, and effectively patch in a debian/ directory. New versions start out in unstable, and after a duration in unstable without serious bugs, that version replaces the old version in testing. The purpose of this is to catch the sort of bugs we saw in Xournal upstream before they cause widespread grief.

Another thing to look at is the June 3rd version in Debian unstable. It has two versions pointing at it. This is because it inherits both the changes from upstream, and the changes that were made in packaging the program for Debian. It is possible that some changes in one source conflict with another. This might happen because Debian patched a bug fix one way, while upstream applied a different fix, for example. In this case the solution is to drop the patch, but sometimes the fix is more complicated. This is what I call the package merge problem in distributions. This is essentially why Debian maintainers hate source code with a debian/ directory provided, since it can cause a conflict with their own packaging efforts.

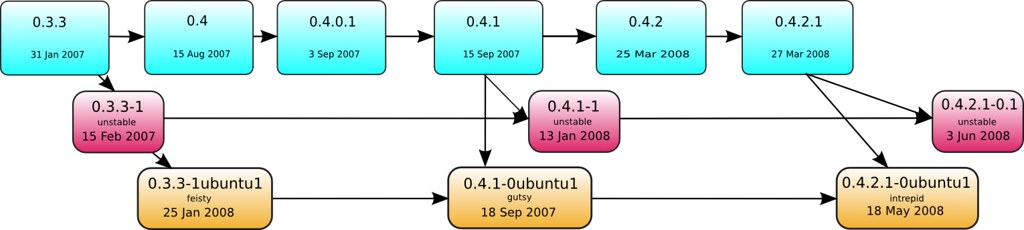

If the above diagram was confusing, the one below may make you physically dizzy (and it doesn't even contain SRU or Backports!):

That's how Ubuntu works. Blue is still upstream, red is still Debian unstable, and Ubuntu now is gold. Feisty, Gutsy, Hardy and Intrepid are all Ubuntu stable releases; the *buntu flavors all put their packages in these same repositories. They largely all share the same kernel, the same X11 server etc; they just install different packages from those repos by default. This diagram doesn't depict a Hardy version of Xournal because it was a sync from Ubuntu itself--Ubuntu just copied the source from Gutsy into Hardy and rebuilt the whole shebang without really looking at it. Many packages in the "universe" categories do the same thing, except from Debian; there is a script to do this automatically as long as Ubuntu has made no changes to the package in the last release.

This diagram traces the Ubuntu Xournal package to its Debian origins, which are a long ways back. Here, notice that only Feisty derives from Debian. Effectively, Ubuntu has forked this package. This is where distributed version control might make cherry picking patches simpler for Debian, Ubuntu and even Xournal, who's author has reasonably lamented the long lead times. DVCS like bzr or git allow everyone to easily share individual commits within a branch with one another. Debian and Ubuntu source code often seems hidden behind walls, smoke and mirrors; DVCS also provides a commonly understood method of accessing it to upstream, who may want to investigate a heavily reported bug that only Ubuntu users seem to report.

In addition, DVCS also makes it easier for new contributers to participate. Current practice for people without upload access is to grab the source package with apt-get, apply a fix and then generate a "debdiff", attach it to a bug report in LP, and subscribe the appropriate teams. Then the maintainers view the debdiff, apply it, and upload to the build system for deployment. DVCS can make all that happen faster, potentially allowing groups like MOTU to work their magic on more packages and bugs.

So distributed version control is important; Is bzr the right pick?

We might want to know what's popular right now, since DVCS exhibits network effects. Romain Francoise has a very timely graph of Debian package version control system popularity:

SVN is the runaway winner here, but for both Ubuntu and Debian's sake, I don't anticipate this to last. SVN doesn't do enough to help developers with the merge problem. Git is quickly on the move, while bzr is standing still when it comes to adoption. The elephant in the room in this graphic is packages with no version control whatsoever. I imagine that widespread DVCS in Ubuntu is expected to lead to more adoption within Debian. The graph also doesn't distinguish between packages who keep the whole source code in revision control versus those that only keep the debian/ dir.

That report comes on the coattails of discussion at FUDCon on Fedora VCS selection and a rather sad commentary from a Fedora developer (Lennart Poettering):

Yes, with CVS, SVN and GIT I think I have learned enough VC systems for now. My hunger for learning further ones is exactly zero. Let me just code, and don't make it hard for me by asking me to learn your favorite one, please.

Fedora making a unilateral package VCS decision could have consequences downstream. A short conversation can be seen on Planet GNOME about the possibility of moving to Git for code hosting, causing some new edits to DistributedSCM in the meantime. The debate over VCS is not new but Keith offered an insightful gem:

[M]ost of the group will just not bother, and will end up choosing essentially randomly, with a slight bias to whatever is most familiar

This fits well with the Debian VCS-* graphic -- most packages choose nothing, or SVN. Well, if formats matter to enlightened despots, how does bzr stack up against DVCS champ git? To figure this out, I've asked my friend Andy Rueder, who spent a good deal of time digging into git and documenting commands and options:

< aeruder> i've always been a big fan of git due to the simplicity of the repository and the fact that the kernel guys are using it

< aeruder> git is very simple as far as repository format goes... every file has a sha1 from its content, a tree (directory) contains sha1's of files and sha1's of other trees, and a commit simply contains a message, and the sha1 of 0 or more parents and the sha1 of the tree associated with it

What I think this means is that there isn't a whole lot to change about the storage format, and it shows. Daniel Stone, former Ubuntu X maintainer and deadly code ninja, has said of bzr:

bzr fails because I try to clone stuff, and it says, 'oh, you have 0.13, we changed the revision yet again and you need 0.18, but good luck finding anything newer than 0.15'.

This is probably the greatest point I've seen against bzr so far. I haven't personally used either bzr or git seriously, but my impression from those who have is that bzr is still difficult with version compatibility. It seems that, if Bazaar is to be king, "stable" should be shortly added to the front page list of bullet points, so distributions can get tools into the hands of developer-users that aren't hopelessly outdated.

Comments !